Support Your Microbiome

for Better Immune Health

Mindd Foundation

The human microbiome is home to about 100 trillion bacteria and other microbes. Understanding how to maintain the microbiome is important to practically every aspect of human health:

- To protect against germs and maintain the immune system

- To break down food to release energy

- To utilize nutritional elements to maintain body functions and health

Immunity Begins in the Gut

The intimate relationship between individuals and their guts is best reflected in their immunity. Immune health begins in the gut.

The presence or absence of infection and disease often depend on the makeup and activity of the individuals’ hidden bacteria in their gut. So, while their presence may not be readily known, good gut flora is an essential part of a healthy life.

Learning to Live with Beneficial Bacteria

Learning how to support beneficial bacteria in the gut is an important challenge to maintain a healthy body.

Accurate, and in many ways, simple tools can provide support for better gut health. The purpose of this guide is to provide knowledge and tools for a 360-degree view of how microbes are linked to overall health:

- Defining the microbiome and its importance

- Understanding how the microbiome impacts infants

- Supporting or suppressing the microbiome through diet

- Pharmaceutical drugs that attack the microbiome

- Diseases caused by microbiome imbalance

- More tools for a stronger microbiome

Defining the Microbiome and its Importance

A common metaphor used to describe the microbiome is that of a garden. Gardens may consist of vegetables, flowers, plants, or all of the above; and they each serve a purpose. Specific beneficial factors, like water and sunlight, promote the garden to grow whereas harmful factors, like weeds and predators, slow or prevent growth.

The microbiome extends beyond the gut to other organs and regions of the body such as the skin, mouth, and vagina. Yet, the most significant population of microbes, (or flowers in the garden), reside in the gut—about 100 trillion to be exact.

The Gut Works Hard to Maintain Microbiome Health

A large proportion of the human microbiome is in the gut. Collectively referred to as the “gut microbiome,” this has been the focus of numerous research studies in recent years.While the good bacteria, yeasts, fungi, viruses, and protozoans that make up the gut microbiome work hard in digesting food into nutrients, sequestering toxins from the bloodstream, and making vitamins for energy and other biological processes, research continues to reveal additional acts in the gut microbiome’s repertoire.

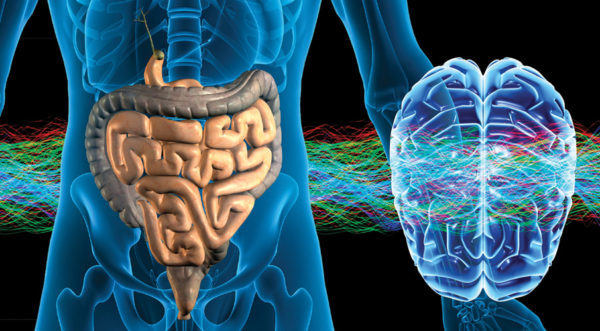

The Gut and Brain are Intimately Connected

The gut and brain are intimately connected, resulting in one environment affecting or, in many cases, influencing the other. The brain’s regulation of gastrointestinal and immune activities ultimately regulates the composition of microbes in the gut. Bacteria in the gut produce by-products from their usual functions which eventually act as signals to the brain. This dual communication drives individuals’ mood and behavior as well as the degree of permeability in the gut lining and blood-brain barrier.

Understanding How the Microbiome Impacts an Infants’ Health

It takes some time to accumulate 100 trillion beneficial microbes in the gut. This fact has led researchers to explore the actual foundation of the gut microbiome, and they found it in the birth canal! The vagina represents another rich supply of microbes that contribute to the microbiome, but that supply is at its most abundant during birth. While passing through the birth canal during delivery, babies are inherently bathed in their mothers’ microbes providing them with a microbiome of their own.

However, that early birthday gift from mother is lost when a baby is delivered via C-section.

Childbirth by C-Section is not Always Necessary

Despite their popularity in medical practice, C-sections are not always essential, unless the baby’s or mother’s life is at risk. C-section babies have a smaller microbiome and less diversity within their microbiomes than babies born vaginally. Accordingly, as they grow older, C-section babies often tend to struggle with allergies, asthma, autoimmune disease, and obesity.

In situations where a C-section is unavoidable, a mother can inform her doctor that she wishes to have her baby vaginally seeded. Vaginal seeding emulates vaginal birth by soaking a sterile gauze pad in the mother’s perineal fluid and wiping the baby down with that gauze pad, instead of antibacterial products, following the C-section. For best results, the pad should be concentrated around the baby’s head, eyes, and mouth.

Protect Baby’s Health by Breastfeeding

In addition to vaginal birth, breastfeeding is another gift from a mother to her baby’s microbiome. A sugar called human milk oligosaccharide, or HMO, is the third most common ingredient in breast milk. Although babies cannot digest HMO, the good bacteria found in babies’ gastrointestinal tracts can digest HMO helping them fight off potentially harmful microbes from the environment or even their mothers’ nipples.

Breastfeeding can help protect an infant’s microbiome after it is established during vaginal birth.

Supporting or Suppressing Microbiome Health Through Diet

Following a great start from Mum, the microbiome relies heavily on the diet and every aspect of health influenced by the microbiome lies in the balance. In other words, what individuals eat can either support or suppress their microbiome thereby reducing or increasing their risk of disease, respectively.

Foods that suppress Microbiome Health include:

- Added sugars – found in bread, cereals, condiments, and packaged snacks

- Non-organic beef and poultry – high in omega-6 fatty acids

- Pasteurized dairy products

- Refined carbohydrates and processed grains

- Refined cooking oils (i.e., canola, corn, soybean) – high in omega-6 fatty acids

- Trans and hydrogenated fats – found in fried and processed foods

These foods harm the microbiome because they induce inflammation in the gut producing imbalances in appetite, fat storage, hormone production, and nutrient withdrawal.

Foods that support Microbiome Health include:

- Cage-free pastured eggs, wild-caught fish, grass-fed beef or poultry – high in omega-3 fatty acids, protein, zinc, selenium, and B vitamins

- Fresh vegetables – high phytonutrient content

- Healthy fats (i.e., grass-fed butter, coconut oil, extra virgin olive oil, nuts/seeds)

- Herbs, spices, and teas

- Probiotics – good bacteria that repopulate the gut

- Red wine and dark chocolate (in moderation)

- Unrefined grains, legumes/beans

- Whole fruit – potent antioxidants, resveratrol, and flavonoids

These foods benefit the microbiome because they fight inflammation in the gut-producing balances in appetite, fat storage, hormone production, and nutrient withdrawal.

Health-Promoting Recommendations for the Microbiome

For vegetables, fruit, herbs/spices/teas, and beans, here are some recommendations worthy of attention:

- At least 4-5 daily servings of vegetables, including – beets, broccoli, cabbage, carrots, collard greens, kale, sea vegetables, spinach, squash, and onions

- 3-4 daily servings of apples, blackberries, blueberries, cherries, grapefruit (pink or red), nectarines, oranges, pears, plums, pomegranates, and strawberries

- Basil, ginger, green tea, oregano, organic coffee, thyme, and turmeric

- Anasazi beans, adzuki beans, black beans, black-eyed peas, chickpeas, lentils, black rice, amaranth, buckwheat, quinoa

Unlike other physiological changes in the body, research shows that the gut microbiome responds very quickly to changes in diet—that is, within three or four days! So, committing to a healthier, microbiome-friendly diet can turn gut health as well as overall health around in an astonishingly short period.

Pharmaceutical Drugs to Avoid to Maintain Good Microbiome Health

Pharmaceutical drugs do come with warning labels stating their side effects, but “compromised gut health” never makes the list. Instead, the words “increased risk of infection” are commonly used. Either way, be aware that many prescription drugs disturb the gut microbiome.

Common pharmaceutical drug challenges come from:

- Antibiotics which wipe out good as well as harmful bacteria and can contribute to bacterial resistance

- Antibacterial products, like hand soaps, hand sanitizers, and household cleaners, that contain triclosan and also contribute to bacterial resistance

- Hormone therapy drugs, such as birth control pills, which interrupt hormone production in the gut

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which suppress acid secretion in the body thereby altering 20 percent of the gut microbiome and are now considered as harmful as antibiotics

- Birth Control Pills – oral contraceptives impact gut flora and adversely affect estrogen metabolism

Caution: Antibiotics in Food Products

Be careful not to overlook antibiotics that may be consumed in food products, mainly from animals raised non-organically in factories or elsewhere. Similar to C-sections, antibiotics should be avoided at all costs unless it is a matter of life or death. For less traumatic infections, like urinary tract infections, D-mannose serves as an excellent antibiotic alternative. Ask an Integrative Health Practitioner for more information.

Many Diseases are Caused by Microbiome Imbalance

Researchers have found that up to 90 percent of all diseases can be traced in some way back to the gut microbiome. These diseases are classified as:

- Allergies and food sensitivities

- Asthma or respiratory infections

- Autoimmune – arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), leaky gut syndrome

- Brain disorders – Alzheimer’s, dementia, seizures, stroke

- Cancer of the brain, breast, colon, pancreas, prostate, or stomach

- Learning disabilities – ADHD, autism

- Mood disorders – depression, anxiety

- Obesity or excessive weight gain

- Reproductive issues or infertility

Microbiome Warning Signs of Inflammation

It is the low-grade build-up of inflammation that leads to these diseases; so, a gut microbiome in trouble can initially manifest as any of the following signs and symptoms:

- Abnormal bowel movements, such as constipation, diarrhea, or bloody stools

- Acne, rashes, or other inflammatory skin conditions

- Frequent viral infections (i.e., the common cold)

- Indigestion, such as bloating, gas, or acid reflux

- Joint and muscle pain

- Low energy or fatigue

- Respiratory infections, stuffy nose, or difficulty breathing

Specific lifestyle changes like lowering stress and exercising more can alleviate these health symptoms. Even supplementing coenzyme Q10, carotenoids, omega-3 fish oil, selenium, or vitamins C, D, and E can offer relief. Yet, optimizing the diet and its impact on gut health are the most vital way to keeping those diseases at bay.

Contact an Integrative Health Practitioner for specific recommendations.

Psychobiotics for the Microbiome can Improve Mood Disorders

Some of the latest gut microbiome research is examining the possible use of probiotics as a treatment for anxiety, depression, and other mood disorders. These probiotics, sometimes called psychobiotics, consist of many of the beneficial bacteria found in yogurt, but instead are customized to fill the needs of whatever individuals lack in their gut microbiome.

More Tools for a Stronger Microbiome

Sometimes how food is consumed is just as important as the food itself. Thus, some additional tools for building a stronger microbiome are:

- Allot 75 percent of your plate to vegetables and plant-based foods

- Make sure some of those vegetables are fermented (i.e., sauerkraut, kimchi, tempeh, or miso)

- Consume all animal protein minimally and at varied intervals

- Drink bone broth often

Tools 1 and 2 maximize the intake of fiber, which serves as a prebiotic for the gut microbiome. (Think of prebiotics as plant food for a garden.)

Tool 3 minimizes the intake of potentially carcinogenic metabolites

Tool 4 rebuilds and protects the gut lining

Likewise, avoid smoking, reduce alcohol intake, use natural cleaning products in the home, and switch to all-natural beauty and skincare products.

‘Borrowing’ a Healthy, Balanced Gut Microbiome

Finally, if diet and lifestyle changes do not restore the gut microbiome to where it needs to be, fecal microbiota transplants have proven successful for many individuals. This process of “borrowing” from an individual’s healthy, balanced gut microbiome is not as hard as it may sound, but it should be performed by a professional only after a rigorous screening process has been completed. Contact an Integrative Health Practitioner for further details.

References

Axe, J. (2018). Gut bacteria benefits: Could better bacteria actually cure your condition? Retrieved from https://draxe.com/gut-bacteria-benefits/

Axe, J. (2018). The human microbiome: How it works + a diet for gut health. Retrieved from https://draxe.com/microbiome/

Feltman, R. (2013, December). The gut’s microbiome changes rapidly with diet. Retrieved from Scientific American at https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-guts-microbiome-changes-diet/#

Fleming, A. (2017, November). Is your gut microbiome the key to health and happiness? Retrieved from The Guardian at www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2017/nov/06/microbiome-gut-health-digestive-system-genes-happiness

Hyman, M. (2017, April). How to fix your gut bacteria and lose weight. Retrieved from The Huffington Post at https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/how-to-fix-your-gut-bacte_b_9318312.html

Mercola, J. (2017, January). The microbiome solution – healing your body from the inside out. Retrieved from https://articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2017/01/29/microbiome-solution.aspx

Schmidt, C. (2015, March). Mental health may depend on creatures in the gut. Retrieved from Scientific American at https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/mental-health-may-depend-on-creatures-in-the-gut/

Shreiner, A. B., Kao, J. Y., & Young, V. B. (2015). The gut microbiome in health and in disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol, 31(1): 69-75. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000139